by P.A. Madison on January 25th, 2016

I want to mark John A. Bingham’s belated January 21 birthday with some of his most significant quotes from 1866 thru 1875 I have come across over the years from such sources as Congressional Globe, House Reports, public speeches and letters. Some will be an eye opener since they are so contrary to what scholars and courts improperly attribute to him in terms of constitutional changes in late 20th century.

“The words ‘citizens of the United States,’ and ‘citizens of the States,’ as employed in the fourteenth amendment, did not change or modify the relations of citizens of the State and nation as they existed under the original Constitution.”

“This guarantee is of the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States in, not of, the several States.”

“That all citizens shall be forever equal, subject to like penalties for like crimes and no other.”

“I ask that South Carolina, and that Ohio as well, shall be bound to respect the rights of the humblest citizen of the remotest State of the Republic when he may hereafter come within her jurisdiction.” Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on May 14th, 2012

The recent Ninth Circuit en banc decision in Gonzalez v. Arizona illustrates current erroneous understanding of the Elections Clause under Section 4 of Article I. At issue in this case was Arizona’s Proposition 200 that required prospective voters in Arizona to provide proof of U.S. citizenship in order to register to vote in both State and Federal elections, along with the requirement of registered voters to show identification to cast a ballot. Additionally, Proposition 200 required the County Recorder to “reject any application for registration that is not accompanied by satisfactory evidence of United States citizenship.”

The court held Arizona’s Proposition 200 was preempted by the Federal National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) because the NVRA provides that “[e]ach State shall accept and use” the Federal Form “for the registration of voters in elections for Federal office.” The court saw Proposition 200 creating a conflict with the NVRA because Arizona could reject the use of the Federal Form to register to vote in Federal elections due to insufficient proof of citizenship.

Arizona’s Proposition 200 raises no constitutional issues or is in conflict with any valid federal law for the simple reason the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 is void due to the lack of any authority to impose voter registration standards upon the States for Federal elections.

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on March 19th, 2012

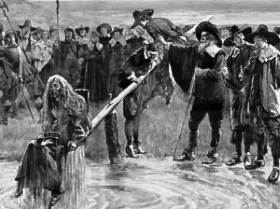

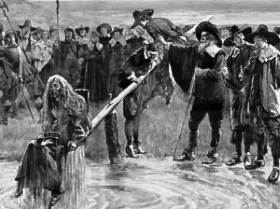

Summary: The prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments is a check against extralegal tribunals or discretionary acts of judges in imposing illegal and cruel punishments that are unknown to established law as practiced under the infamous court of Star Chamber.

I thought it was about time to address the well-established ancient understanding of the Eighth Amendments provision for “cruel and unusual punishments” since it is obvious current jurisprudence has no fundamental clue to its constitutional purpose. Most judges today probably will be surprised to learn it is directed at them as security against imposing discretionary punishments not sanctioned by fixed law than anything to do with established law itself.

I thought it was about time to address the well-established ancient understanding of the Eighth Amendments provision for “cruel and unusual punishments” since it is obvious current jurisprudence has no fundamental clue to its constitutional purpose. Most judges today probably will be surprised to learn it is directed at them as security against imposing discretionary punishments not sanctioned by fixed law than anything to do with established law itself.

Cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment is rather easy to understand because of the fact it was copied verbatim from the English Bill of Rights of 1689. The English Bill of Rights tells us the evil remedied by the words “cruel and unusual punishments” was to prohibit the practice of “illegal and cruel punishments,” because such punishments were “utterly and directly contrary to the known laws and statutes and freedom of this realm.”

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on January 8th, 2012

Since recess appointments have been getting a great deal of press attention lately, and because it appears Obama and Congress don’t have a firm understanding of the actual text and history of the clause; I thought would quickly explain the constitutional purpose of the recess clause beginning with its earliest roots.

The recess clause to the Constitution was proposed by North Carolina delegate Richard Dobbs Spaight during the federal convention, who thought it might be a good idea for the federal Constitution to mimic the North Carolina Constitution in regards to recess appointments.

Recess appointments served an important function because the power to make appointments was generally shared by both the executive and the legislature who might have long recesses. It was common for many State legislative bodies to have biennial sessions, leaving potentially important vacancies to occur during the recess of the legislative body, such as sheriffs and constables, to go for some time before being filled if there was no exception for the executive to make appointments while the legislature was not in session.

The language of the federal recess clause bears this truth in the words, “The President shall have the Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.” Obviously appointing someone to fill a vacancy that is already before the Senate for their advice and consent cannot be considered a vacancy occurring during the next recess of the Senate. An 1845 Attorney General opinion confirms this: “If vacancies are known to exist during the session of the Senate, and nominations are not then made, they cannot be filled by executive appointments in the recess of the Senate.”

Alexander Hamilton explained the recess clause this way:

The ordinary power of appointment is confined to the President and Senate jointly, and can therefore only be exercised during the session of the Senate; but as it would have been improper to oblige this body to be continually in session for the appointment of officers and as vacancies might happen in their recess, which it might be necessary for the public service to fill without delay, the succeeding clause is evidently intended to authorize the President, singly, to make temporary appointments “during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session.”

Hamilton added in 1799 that, “[i]t is clear, that independent of the authority of a special law, the President cannot fill a vacancy which happens during a session of the Senate.”

In conclusion, it would be rather absurd to treat the recess clause as a tool for the President to use to circumvent the Senates constitutional advice and consent role in approving appointments to fill vacancies that occur only during a recess. Appointments for vacancies that occur during a Senate session can only be filled through the Senates advice and consent. The senate or court could remedy any illegal appointments to fill vacancies by the President that occur while the Senate is in session, or while the appointment is already before the Senate and the Senate goes into recess, by immediately declaring the appointment void.

by P.A. Madison on November 4th, 2011

Justice Thomas pointed out what many should already know from his lone dissent from the court’s denial of certiorari in Utah Highway Patrol Association v. American Atheists Inc. on Monday: Federal Establishment clause jurisprudence is “in Shambles.” The court’s refusal to hear the case brings to an end a lawsuit that has been contested since 2005, leaving Establishment Clause jurisprudence muddy as ever:

Today the Court rejects an opportunity to provide clarity to Establishment Clause jurisprudence in shambles. A sharply divided Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit has declared unconstitutional a private association’s efforts to memorialize slain police officers with white roadside crosses, holding that the crosses convey to a reasonable observer that the State of Utah is endorsing Christianity.

Thomas mocks the court over how the Lemon/endorsement test has been selectively applied to cases over the years leaving the question of “constitutionality of displays of religious imagery on government property anyone’s guess.” He draws attention to the majority ditching the Lemon/endorsement test in upholding a Ten Commandments monument located on the grounds of a state capitol in Van Orden, 545 U. S. 677. On the same day Van Orden was announced, the court decides to apply the Lemon/endorsement test in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union of Ky. to find a display of the Ten Commandments in a courthouse unconstitutional.

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on October 14th, 2011

“[A]ssembly to be peaceable, the usual remedies of the law are retained, if the right is illegally exercised.” —William Rawle

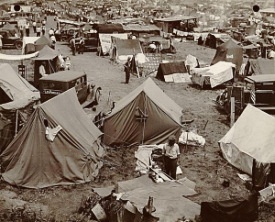

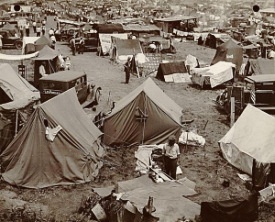

I wish to briefly address the assertion the folks occupying Wall Street – and elsewhere – are merely exercising their First Amendment right to peaceful assembly. The constitutional provision to peaceably assemble extends no further than to peacefully assemble for a lawful purpose such as circulating a petition to present to government. It is not a requirement for government to provide a public soapbox in order for groups to publicly advocate some policy or protest some action through public disturbance, or disruption of daily life of the public.

I wish to briefly address the assertion the folks occupying Wall Street – and elsewhere – are merely exercising their First Amendment right to peaceful assembly. The constitutional provision to peaceably assemble extends no further than to peacefully assemble for a lawful purpose such as circulating a petition to present to government. It is not a requirement for government to provide a public soapbox in order for groups to publicly advocate some policy or protest some action through public disturbance, or disruption of daily life of the public.

Books are filled with court holdings since the founding that says the right to assemble gives no group of people a right to “commit violence upon persons or property,” or “resist execution of the laws,” or “to disturb public order.”

If laws for restricting camping, the hours for which public property may be occupied, or even how many persons may occupy a given space, have always been a legitimate municipal exercise, what makes anyone think either State or Federal constitutions exempts persons from such laws?

Tucker said of the the federal right to assemble was “to protect the petitioners in their right to get up the petition, circulate it for signatures, and have it presented.” The Supreme Court case of United States v. Cruikshank observed the purpose of assembly was for petitioning government: “The right of the people peaceably to assemble for the purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress of grievances, or for anything else connected with the powers or the duties of the National Government.”

In England, the right of assembly existed from early times and was strictly tied to the right of petitioning Parliament for political purposes, which the crown had always strongly contested. Different acts of the Tudors and Stuarts sought to limit and restrict assembly.

There is a big difference between gathering to draw public attention to some grievance or message through disruption of the public peace and peacefully gathering to address common public concerns and to circulate a petition for signature. The later requires no mob occupation or disruption of the peace or laws.

From a purely historical standpoint, “Occupy Wall Street” is nothing more than rebellion, and as such generally been dealt with by use of the militia to suppress.

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on October 10th, 2011

Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School (“Hosanna-Tabor”) is a religious school in Redford, Michigan who terminated employment of a teacher and commissioned minister named Cheryl Perich after a disability-related leave of absence for narcolepsy. Perich taught a full secular curriculum along with religion and lead students in prayer. Perich filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”), alleging discrimination and retaliation in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”).

Hosanna-Tabor argues the case involves a dispute over religious authority, and the First Amendment doctrine that recognizes a “ministerial exception” removes the school from such litigation because judges would be interfering in the pastoral and religious mission of the school. The Obama Administration argues the “ministerial exception” should not apply when churches or religious schools fire someone in retaliation for asserting their rights under disabilities law.

This case is being paraded as a high stakes First Amendment test over separation of church and state but in reality, it has nothing to do with any enumerated powers invested in the central government over anything touching religion or labor.

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on August 23rd, 2011

Remember that trucking provision under NAFTA (The North American Free Trade Agreement), which was ratified in November of 1993, allowing Mexican trucks to access border States highways by 1995 and to all US highways by 2000? The trucking provision of the agreement has never been fully implemented due to safety concerns of Mexican trucks, which currently are restricted to a 25-mile border zone. This has resulted in retaliatory tariffs by Mexico over this disputed highway access.

In July, the United States and Mexico signed an agreement aimed at resolving this cross-border trucking dispute under NAFTA. While most of the controversy centers on safety concerns, the real concern should be with Congress’ authority to mandate foreign traffic within sovereign State limits.

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on July 8th, 2011

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void. —Section 4 of the Fourteenth Amendment

If I understand the argument currently circulating around the web correctly, the debt limit is unconstitutional under §4 of the Fourteenth Amendment because the failure to service (borrow/pay) public debt would bring the validity of it into question. This does not strike me as having any connection with the textual history behind this section.

Read the full article →

by P.A. Madison on June 30th, 2011

- The Power Described

- The Regulating Power Sought Over Commerce with the States

- Commerce Defined

- Why Nations Regulate their Commercial Intercourse

- Why the Power among the States

- Why Congress Lacks Affirmative Powers over Interstate Commerce

- Confusing Marine Power with the Regulation of Commerce

- Conclusion

The United States Supreme court tells us their “case law firmly establishes Congress’ power to regulate purely local activities that are part of an economic ‘class of activities’ that have a substantial effect on interstate commerce.” In a September 2009 press release, former speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi asserted, “the Constitution gives Congress broad power to regulate activities that have an effect on interstate commerce.”

The United States Supreme court tells us their “case law firmly establishes Congress’ power to regulate purely local activities that are part of an economic ‘class of activities’ that have a substantial effect on interstate commerce.” In a September 2009 press release, former speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi asserted, “the Constitution gives Congress broad power to regulate activities that have an effect on interstate commerce.”

The question explored here is whether such “case law” or public assertions are supported in any way by the history, text and custom of regulating commerce. If it cannot be supported by any factual evidence then it is clearly erroneous and has no place in federal jurisprudence where facts and truth should be held paramount.

History of the organic law of this country conclusively shows beyond any doubt that the regulation of commerce was nothing more, and nothing less, then the act of imposing a tax on articles of import for the sole purpose of restricting or prohibiting their introduction in order to protect or promote local manufactures. Moreover, this was the custom and practice of all nations in regulating commerce with other nations or parts of a nation and no nation ever claimed police powers over another nation or parts of themselves via authority to regulate commerce.

Because regulating commerce and generating revenue is accomplished through the same identical method of imposing a tax, the regulation of commerce “among the several states” was inserted for remedial purposes of preventing States from taxing the trade of other States as well as preventing Congress from doing the same under Section 9.

It will become abundantly clear why James Madison referred to the regulation of commerce “among the several states” as a “negative and preventive provision” and not any power Congress may resort to for “positive purposes” (see Madison letter to Joseph C. Cabell).

Finally, it will be pointed how the court has mistakenly confused marine law of nations with that of regulating commerce, which has introduced erroneous assumptions over the extent of the power.

Read the full article →